This case study was developed for a faculty member in the Physician Assistant (PA) program to help students walk through a patient’s ER visit using progressive disclosure. This was designed to be a group in-class quiz where the students work in small-groups to identify a final patient diagnosis.

Derived from the 18th-century learning style developed by William Heard Kilpatrick; Problem-Based Learning (PBL) is grounded in the constructivist learning theory where the learning occurs when students are actively engaged in the learning process and content. The modern approach to PBL was reintroduced by Canadian medical schools which brought patient case studies (case-based learning, or CBL) into the classroom. (Pecore,2015) As technology has evolved, e-learning is increasingly becoming an integral part of contemporary medical education. (Ellaway, 2008).

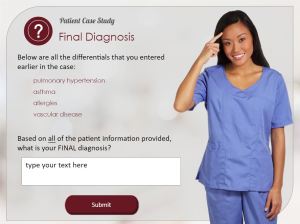

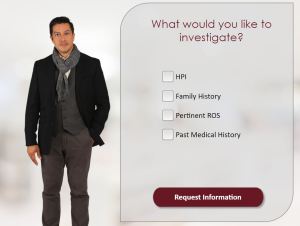

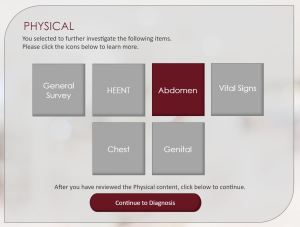

As a graduate university in health professions education that has a shared vision of educational innovation, the creation of case-based e-modules were developed to supplement student learning within the university’s physician assistant program. Throughout the course students interact with a series of patient case study e-modules that simulate a standard medical office visit within an online environment. The gamified e-modules enable the students to review patient history, complete a physical examination, request lab diagnostics, communicate differential diagnosis, and suggest a patient treatment plan. Differential diagnoses are examined at each phase throughout the simulated visit. Upon completion of the case the student is presented with the patient’s final insurance bill, as well as a recap of their progress throughout the case. The professor can evaluate the student’s thought process in the form of their progressive differential diagnoses which is printed at the conclusion of the e-module case study.

Gamification techniques are added into the creation of the e-module my means of a generated insurance invoice upon completion of the case. According to Orlando (2016), students learn best when they are challenged and working toward a goal. The ending goal of the CBL e-module is to provide proper and cost-effective healthcare to the patient. The student is rewarded for correct choices by generating revenue for the medical clinic. However, in contrast, if the student selects incorrect medical treatment options a negative amount is added to the insurance invoice. This gamification pedagogy helps students to understand that in real-world scenarios not all diagnostics are covered by the patient’s insurance plan and therefore the choices they make should be intentional.

Case-based learning has been “shown to enhance clinical knowledge, improve teamwork, improve clinical skills, improve practice behavior, and improve patient outcomes.” (McLean, 2016). One day students will be employed in the healthcare field and working with patients, and therefore their education should try to simulate those patient case-based scenarios. By introducing the patient symptoms in these case-based scenarios the students can directly relate the diseases to the symptoms, rather than the traditional student approach of mass-memorization. (Jhala, 2019). The e-modules developed give the students a deep-learning approach by allowing the students to be presented with a holistic approach to patient care, from the complaint to the social aspect of the patient’s life. According to Jhala (2019), “If students applied the deep-learning approach …their knowledge would reach higher echelons…”

This workshop featured a collaborative effort between the Instructional Designer for the Center for Academic and Professional Enhancement, and the subject matter expert (SME) of the pediatrics course.

REFERENCES

Dunleavy, Gerard, et al. “Mobile Digital Education for Health Professions: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis by the Digital Health Education Collaboration.” Journal of Medical Internet Research, vol. 21, no. 2, 2019, doi:10.2196/12937.

Faux, Margaret, et al. “Who Teaches Medical Billing? A National Cross-Sectional Survey of Australian Medical Education Stakeholders.” BMJ Open, vol. 8, no. 7, 2018, doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020712.

Ginzburg, Samara B, et al. “Integration of Leadership Training into a Problem/Case-Based Learning Program for First- and Second-Year Medical Students.” Advances in Medical Education and Practice, Volume 9, 2018, pp. 221–226., doi:10.2147/amep.s155731.

Graaff, Erik de., and Anette Kolmos. Management of Change: Implementation of Problem-Based and Project-Based Learning in Engineering. Sense Publishers, 2007.

Jhala, Meenakshi, and Jai Mathur. “The Association between Deep Learning Approach and Case Based Learning.” BMC Medical Education, vol. 19, no. 1, 2019, doi:10.1186/s12909-019-1516-z.

Juneau, Karen R. “Learning Through Projects.” Encyclopedia of Information Technology Curriculum Integration, pp. 533–540., doi:10.4018/978-1-59904-881-9.ch087.

Mclean, Susan F. “Case-Based Learning and Its Application in Medical and Health-Care Fields: A Review of Worldwide Literature.” Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development, vol. 3, 2016, doi:10.4137/jmecd.s20377.

“Online Case-Based Learning Design for Facilitating Classroom Teachers Development of Technological, Pedagogical, and Content Knowledge.” European Journal of Contemporary Education, vol. 6, no. 2, 2017, doi:10.13187/ejced.2017.2.308.

Pecore, J. L. (2015). From Kilpatrick’s project method to project-based learning. International Handbook of Progressive Education, 155-171.

Software:

Articulate Storyline

Created:

2019

Client:

Physician Assistant (PA) Professor